A Twin Approach To Getting New Projects Off To A Great Start

Lessons from the US Special Forces and the magic of the ‘pre-mortem’ combined to increase the odds of success

It is generally acknowledged that many businesses fail to fully meet the objectives of the projects and strategies that they set out to deliver. Indeed, poor project management is assessed to cost businesses up to 14% of funds invested. There are many reasons why this is the case including: no clear view of priorities, overstretched staff and no project management training or consistent ways of working. Communications, alignment and the development of an appropriate rhythm of execution are all also essential components of success. To solve all the issues that a business might face in executing strategy can be a daunting prospect. Whilst, at Skarbek, we are used to helping across this full range of strategy implementation; we thought it worth sharing the combination of two techniques which can quite quickly focus energy and build momentum towards better outcomes, saving time and money and setting the conditions for future growth.

The first method we would recommend has its beginnings in the world of Special Forces operations and centres on the identification and rapid implementation of priority tasks to shift the balance of probability towards success.

Special Forces teams are typically small. The longer they are on the ground the more vulnerable they are, and thus in operations they need to be utterly focused, and fast. Time is of the essence. Admiral William McRaven, a former US Navy Seal and head of US Special Forces carried out a retrospective analysis of over 40 Special Forces operations. In all 40 operations there were a number of objectives to be achieved, but importantly, these objectives weren’t equal in their contribution to a successful outcome. McRaven found that the common success factor was to limit the number of objectives as far as it was possible, identify one or two that would have the most significant impact, and pursue them first and fast. Once these important objectives had been achieved, the vulnerability of the team on the ground was decreased and a line was crossed – a line identified by McRaven as the ‘line of relative superiority’ – where the mission was more likely to succeed than it was to fail.

Ref: McRaven SpecOps

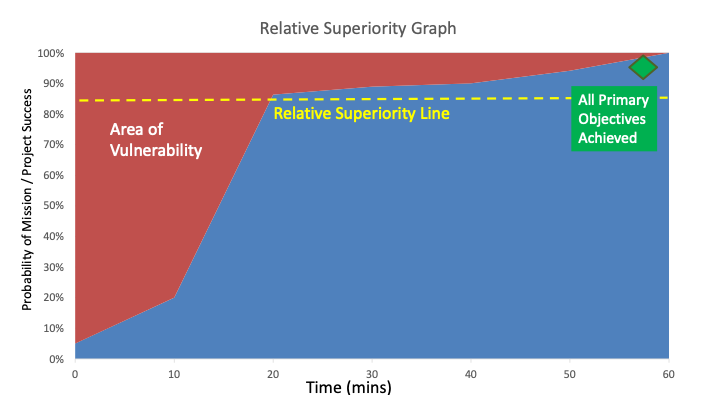

In the graph above, the probability of the mission’s success is measured on the vertical axis and time is measured on the horizontal axis. The area coloured red is the area of vulnerability, where the Special Forces are most at danger. In this operation, the first objective was achieved after only 10 minutes and the probability of success immediately leapt to 20%. The second objective was achieved after 20 minutes and took the probability of success up to 85%. At this point the vulnerability of the soldiers was radically reduced and the Relative Superiority Line was crossed, and the mission was more likely to be successful than not. After 60 minutes, all primary objectives were achieved and the mission accomplished.

While the delivery of projects in business may feel a long way from a Seal Team operation, the principle of identifying priority tasks and delivering them through a greater allocation of time, effort and resource is apposite. Focus will shift throughout the life of a project and while a long-term view is also healthy, a strong start to move out of the ‘area of vulnerability’ as soon as possible is a good place to begin.

With the route to success set using the Probability of Success (McRaven) graph we then stress-test the plan for each step to the ‘relative superiority line’. The idea of testing a plan to destruction also has its roots in military planning – it might be called war-gaming or red-teaming. We then use the points of inflection – an accomplishment of a key object as a point of failure as the start point of a simple but highly effective approach called the “pre-mortem”. This is a simple and versatile way to empower a team and to avoid ‘group-think’.

In ‘real-life’ a coroner’s post-mortem looks at a dead body and tries to work out what went wrong – while useful for the living from the perspective of the corpse any findings are too late. A pre-mortem is the hypothetical opposite of a post-mortem in a project context. It comes at the beginning or when the project is ‘in flight’ rather than at the end of a project, so that it can be improved rather than autopsied. Unlike a typical critiquing session, where we ask what might go wrong, the pre-mortem operates on the assumption that the “patient” has died! It starts with a key objective was not achieved, e.g. the stability testing failed or the clinical trial failed to achieve its objectives and so leads us to ask what possibly caused it to fail. This plays a useful psychological trick in that when faced with a ‘failed’ project the team has a licence for both free and honest thought. By shifting the focus from the probability of an event to the management of consequences a richer picture is developed. It changes the mindset from ‘this risk might happen’ and as such is not a priority for our time and engagement to “…this happened”.

With the team facing its ‘failure’ they are asked to list every reason the endeavour went wrong. They are encouraged to be as open as possible, unconstrained by internal politics and to look at the failure from every possible angle – even outlandish reasoning is to be encouraged to try and cover every possibility. With this list in hand, the ‘what if’s’ quantified there then follows a session to work through each identified issue, to recognise the warnings and indicators of potentially damaging events and to find ways to mitigate them.

The primary benefits of the pre-mortem are at least three-fold:

- Firstly, the project plan is strengthened. We may have found we should take immediate actions now to forestall the failure possibility of failure identified in the pre-mortem. Some problems will have been avoided by an honest appraisal of the state of the planning. An identification of the warnings signs of danger will ensure that as other issues emerge they are recognised and dealt with swiftly. When other unidentified issues occur, a problem-solving mentality has already been adopted and rehearsed, the team are more resilient.

- Secondly, the leader is called upon to listen to their team, to make judgements about their advice, to run with some ideas and discard others. By understanding the characters in their team and their thinking they will be better placed to run the project. By having the confidence to deal with criticism of their plan in the ‘safe’ environment of the pre-mortem they create a more agile and dynamic force.

- Thirdly, from the perspective of the team who have been included in the development of the plan they can take some ownership of what they have been asked to deliver. They have a stake in the outcome and have been empowered to add value. A team where dialogue is encouraged and a practical, pragmatic and dynamic approach to problem solving is the norm is far more likely to succeed.

As businesses, we are constantly being asked to do more with less, to deliver the seemingly impossible against the odds. There is no doubt that the combination of focus and speed that Admiral McRaven recognises as crucial to success in SF raids can also help to boost the start of a project and build the momentum and confidence that will drive subsequent success. Alongside this critical focus must also sit the testing and interrogation of the plan and the pre-mortem provides a great way of quickly analysing the thinking behind a plan whilst also developing a more effective team culture.

Admiral McRaven also recommends that we must ‘get over being a sugar cookie’, that we sometimes have to ‘slide down obstacles head first’ and that we should ‘start singing when we are up to our necks in mud’, but we will tackle all that advice on another day!